Willard Says……

Suction bypass valves were evidently much on the mind of one man starting over 60 years ago. Periodically, for 25 years starting in 1941, Mr. D. L. Hofer was granted a string of patents for a “Relief Valve Control”. His ideas served the hydraulic dredging industry well for decades.

Others came along and aped Mr. Hofer’s ideas on how to prevent or reduce dredge pump cavitation, however, his name was generic for a “suction bypass valve”.

Mr. Hofer’s goal was to develop and market a system that would prevent cavitation by correcting conditions that threatened to cause the dredge pump to cavitate. His “valve” guarded against low vacuum (gas entering the suction), high vacuum (suction inlet buried in solids), low discharge pressure (first sign of cavitation) or high discharge pressure (pipeline may be plugging). The operator set limits for these four parameters with enough latitude between them to accommodate normal production.

Each time a setpoint was exceeded, a bypass valve mounted under water on the suction pipe would snap open and admit water. Water entering the suction pipe assured that the pump was relieved of any condition that may have resulted in cavitation. Production also went into the dumper when a flood of clear water entered the dredge system. One producer said, “Every time the valve opens, the belt soon goes empty.” As soon as normal setpoint values were restored the valve would go shut over an adjustable period of time—perhaps 10 to 15 seconds—and normal production would resume.

Over the years, I have seen a number of these valves as well as the aped versions. Most were plagued by the same set of problems. The bypass valves were the wrong size, the wrong type and installed in the wrong location. The setpoint circuitry was subject to nuisance tripping. The pressure sensing taps and connecting tubing was subject to plugging. These were mechanical problems that could have been corrected.

Case History

We came across one particularly inept attempt to utilize a bypass valve on a two- year-old ladderpump dredge manufactured by a competitor when the owner asked us to help solve his problem of lousy production. The manufacturer had fired off his full quiver of excuses and missed the mark every time; now, the owner was getting desperate.

The dredge did not have a velocity meter so we installed one.

The dredge did not have a vacuum gauge so we installed our LADDERVAC; a differential pressure gauge that indicates the reduction of pressure in the ladderpump inlet port relative to the ambient pressure outside the inlet port.

We noted that the dredge did have a bypass valve installed in the suction pipe, but it took a while to fathom how it worked. There seemed to be such a dumb principle at work that we had to keep checking to be sure that we hadn’t missed something. Perhaps our competition had found the Rosetta stone of bypass valve hieroglyphics. But no, it was just as it appeared—a dopey idea.

The bypass valve opened each time the operator raised the ladder.

Evidently the design engineer had had a brainfart; how else could he have spawned such a goofy concept of bypass valve control? How else could he have gotten the idea into his head that density always needs diluting when the ladder is raised?

The biggest impediment to production was the rotary cutter; a severe misapplication because the deposit had a lot of oversized rock. The rotary cutter was ineffectual, could not mine to the bottom of the deposit, could not support adequate production and suffered repeated shaft breakage. The operator had to work his tail off to maintain meager production. All that maneuvering meant that the ladder went up and down a lot. The bypass valve came open a lot; every time he raised the ladder. Each time the ladder went up, production—such as it was—went down.

The owner installed a CONVAC and replaced the rotary cutter with a linear cutter. Production soared, the operator started enjoying his job, the chain dug down to the desired depth and the owner has prospered happily ever since.

Discharge Pressure to Monitor Velocity?

In the days before (pre-1980) inexpensive velocity meters became available, the idea of monitoring discharge pressure to guard against pipeline plugging may have been valid. An increase in discharge pressure could be interpreted as a sign that the pipeline was plugging so the high discharge pressure setpoint was supposed to be set 4 or 5 psi higher than the normal operating pressure. If the pressure exceeded the setpoint, the bypass valve opened and diluted the flow, the pressure came down, the valve shut and normal pumping resumed. Because such a slight increase in discharge pressure could result from any of several causes other than plugging, this was another source of nuisance tripping and more lost production.

I know from first hand experience that persuading producers to buy a velocity meter to guard against pipeline plugging can be a hard sell. I was successful in selling over 200 velocity meters over a period of several years, but more often, I failed to make a sale.

Bypass valve vendors were even more reluctant to adapt the idea of using velocity to guard against pipeline plugging instead of discharge pressure. I seldom saw a bypass valve that used a velocity meter to guard against plugging.

We saw the value of ideas that Mr. Hofer generated, however, we were also aware of their limitations. Those emergency-type valves prevented cavitation and pipeline plugging by interrupting production. Not a totally positive solution because high, continuous production is the goal. We commenced the search for a better idea.

We were successful in our quest.

A New Concept

For some time there has been a new bypass kid on the block—CONVAC. This proven system leapfrogs clear over the old idea of “relief” and lands on a fresh concept— CONTINUOUS PRODUCTION.

Now production can flourish continuously without fear of plugging the pipeline and without having to constantly maneuver the suction inlet to achieve and maintain vacuum. Now, the operator can relax AND achieve and maintain high production.

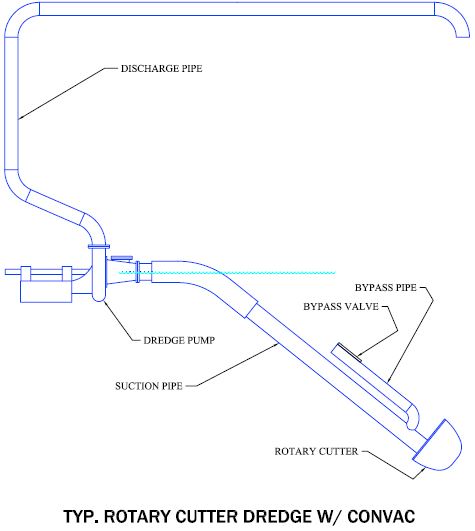

A sketch of a hullpump rotary cutter dredge with a CONVAC system.

With CONVAC the goal is to keep the suction inlet immersed in pumpable solids all the time. CONVAC is designed to insure full, continuous production while in what used to be called a “choke-off “condition. The operator has two jobs: keep the suction inlet immersed in pumpable solids and tap a touch pad now and then. Small vacuum setting adjustments via touch pad maintain flow at the target velocity. CONVAC does the rest. It corrects problems that could interfere with the continuous, regulated intake of solids before the operator knows they exist. It does not get tired and it always is on guard to prevent pipeline plugging. It is relentless!

Well over 100 CONVAC systems are, at this minute, supporting production rates that are 20 to 40 percent higher than would otherwise be possible.

Only those who are afraid of success should pass up the opportunity to learn how they too can enjoy the benefits of CONVAC. Costs nothing to find out.

The profit from increased production will quickly recoup CONVAC’s modest cost; after that, it’s all gravy. CONVAC requires no daily maintenance. It does not eat much; less than three horsepower.

I can state with all modesty that the CONVAC modulating bypass valve is the most revolutionary development in hydraulic dredge mining since the introduction of the ladderpump. It has been “processed”, “pearced”, “maximized” and still commands the land of bypass valves.

CONVAC will do more to jump-start production than any other improvement that can be installed on a dredge.

Comment, question, criticism, information on products mentioned? Contact willard@willardsays.com